(Updated 11/6/24)

It flew for 12 seconds, for a length of 120', with Orville Wright as pilot, December 17th, 1903. A short flight, but in the words of Orville and Wilbur Wright "a flight very modest compared with that of birds, but it was, nevertheless, the first in the history of the world in which a machine carrying a man had raised itself by its own power into the air in free flight, had sailed forward on a level course without reduction of speed, and had finally landed without being wrecked. The second and third flights were a little longer, and the fourth lasted 59 seconds, covering a distance of 852 feet over the ground against a 20-mile wind."(1)

The Wright Brothers had left Dayton on September 23rd and arrived at their camp at Kill Devil Hill, North Carolina on the 25th. So why had the first flight not occurred until December 17th? The answer follows, as told in the words of Orville Wright:

"The first run of the motor on the machine developed a flaw in one of the propeller shafts which had not been discovered in the test at Dayton. The shafts were sent at once to Dayton for repair, and were not received again until November 20th, having been gone two weeks. We immediately put them in the machine and made another test. A new trouble developed. The sprockets which were screwed on the shafts, and locked with nuts of opposite thread, persisted in coming loose. After many futile attempts to get them fast, we had to give it up for that day, and went to bed much discouraged. However, after a night's rest, we got up the next morning in better spirits and resolved to try again.

While in the bicycle business we had become well acquainted with the use of hard tire cement for fastening tires on the rims. We had once used it successfully in repairing a stop watch after several watchsmiths had told us it could not be repaired. If tire cement was good enough for fastening the hands of a stop watch, why should it not be good for fastening the sprockets on the propeller shaft of a flying machine? We decided to try it. We heated the shafts and sprocket, melted cement into the threads, and screwed them together again. This trouble was over. The sprockets stayed fast.

"The first run of the motor on the machine developed a flaw in one of the propeller shafts which had not been discovered in the test at Dayton. The shafts were sent at once to Dayton for repair, and were not received again until November 20th, having been gone two weeks. We immediately put them in the machine and made another test. A new trouble developed. The sprockets which were screwed on the shafts, and locked with nuts of opposite thread, persisted in coming loose. After many futile attempts to get them fast, we had to give it up for that day, and went to bed much discouraged. However, after a night's rest, we got up the next morning in better spirits and resolved to try again.

While in the bicycle business we had become well acquainted with the use of hard tire cement for fastening tires on the rims. We had once used it successfully in repairing a stop watch after several watchsmiths had told us it could not be repaired. If tire cement was good enough for fastening the hands of a stop watch, why should it not be good for fastening the sprockets on the propeller shaft of a flying machine? We decided to try it. We heated the shafts and sprocket, melted cement into the threads, and screwed them together again. This trouble was over. The sprockets stayed fast.

Just as the machine was ready for test bad weather set in. It had been disagreeably cold for several weeks, so cold that we could scarcely work on the machine some days. But now we began to have rain and snow, and a wind of 25 to 30 miles blew for several days from the north.....On November 28, while giving the motor a run indoors, we thought we again saw something wrong with one of the propeller shafts. On stopping the motor we discovered that one of the tubular shafts had cracked!

Wilbur remained in camp while I went to get the new shafts (from Dayton). I did not get back to camp again till Friday, the 11th of December. Saturday afternoon the machine was again ready for trial, but the wind was so light a start could not have been made from level ground with the run of only sixty feet permitted by our monorail track. Nor was there enough time before dark to take the machine to one of the hills, where, by placing the track on a steep incline, sufficient speed could be secured for starting in calm air."(2)

The next day was a Sunday, and there would be no flying on the Lord's Sabbath, not even the first heavier-than-air powered manned flight in the history of the world. As told by Harry Combs, author of Kill Devil Hill, Discovering the Secret of the Wright Brothers, "December 13 was perfection. The skies and the winds were made to order. A warm breeze of 15 miles an hour sighed across the desolate sands. The moment for flight could not have been better. But Orville and Wilbur spent the day relaxing. They caught up on some personal chores, read books, walked the beach. December 13 was a Sunday, and the brothers had given their word to their father they would not break the Sabbath by working."

In a letter written by their father Milton Wright, May 5th, 1912, Milton wrote" They (Wilbur and Orville) close shop Sundays, mostly stay at home, leave no engagements for Sundays- never, unless some subordinate has bargained to have a machine out on Sunday, and then do not more than fill the contract...They believe business should stop one day in seven. They are pure in their speech, they tell only the truth, they are much lied about, they never boast what they are going to do."

As told by Orville Wright in How We Made the First Flight, "Monday, December 14, was a beautiful day, but there was not enough wind to enable a start to be made from the level ground about camp. We therefore decided to attempt a flight from the side of big Kill Devil Hill....We laid the track 150 feet up the side of the hill on a 9-degree slope. With the slope of the track, the thrust of the propellers and the machine starting directly into the wind, we did not anticipate any trouble in getting up flying speed on the 60-foot monorail track. But we did not feel certain the operator could keep the machine balanced on the track.

When the machine had been fastened with a wire to the track, so that it could not start until released by the operator, and the motor had been run to make sure that it was in condition, we tossed up a coin to decide who should have the first trial. Wilbur won. I took a position at one of the wings, intending to help balance the machine as it ran down the track. But when the restraining wire was slipped, the machine started off so quickly I could stay with it only a few feet. After a 35 to 40-foot run it lifted from the rail. But it was allowed to turn up too much. It climbed a few feet, stalled, and then settled to the ground near the foot of the hill, 105 feet below. My stop watch showed it had been in the air just 3 1/2 seconds. In landing, the left wing touched first. The machine swung around, dug the skids into the sand and broke one of them. Several other parts were also broken, but the damage to the machine was not serious. While the test had shown nothing as to whether the power of the motor was sufficient to keep the machine up, since the landing was made many feet below the starting point, the experiment had demonstrated that the method adopted for launching the machine was a safe and practical one. On the whole, we were much pleased."(2)

The next two days were spent making repairs and setting track for a level launching from a "smooth stretch of ground about one hundred feet north of the new building."And so, on December 17th, the four flights were made.

"John Daniels...the coast guardsman who ambled over from the coast guard station...said, 'What are you doing today, Orville?' and Orville Wright, bicycle man of the day, looked up from his funny contraption and smiled, saying nothing. Daniels said, 'Orville got on that contraption and stretched out face down. The little 12-horsepower motor finally was started. Then she started off and rose up in the air just a bit.........The thing came down but it had flown." (3)

Continuing Orville's account, after the fourth flight, "The frame supporting the front rudder was badly broken, but the main part of the machine was not injured at all." (Damaged upon landing on fourth flight of 852 feet). "We estimated that the machine could be put in condition for flight again in a day or two. While we were standing about discussing this last flight, a sudden strong gust of wind struck the machine and began to turn it over. Everybody made a rush for it. Wilbur, who was at one end, seized it in front. Mr. Daniels and I, who were behind, tried to stop it by holding the rear uprights. All our efforts were vain. The machine rolled over and over. Daniels, who had retained his grip, was carried along with it, and was thrown about head over heels inside of the machine. Fortunately he was not seriously injured, though badly bruised in falling about against the motor, chain guides, etc. The ribs in the surfaces of the machine were broken, the motor injured and the chain guides badly bent, so that all possibility of further flights with it for that year were at an end."(2)

As written by Tom Crouch in "The Bishop's Boys", "Daniels, at least, was uninjured. For the rest of his life, he would remind anyone willing to listen that he had survived the first airplane crash. The Wrights and their volunteer crew dragged what was left back into the hangar. The earlier aircraft, the gliders of 1900-02, had simply been abandoned at the site. This time they would ship the remains (of the 1903 Flyer) home to Dayton."(4)

The Flyer remained in the shipping crates, and was stored in the shed building behind the Wright Cycle Shop at 1127 West 3rd Street in Dayton, and there it remained for years, never to be flown again. As the Wrights continued their experiments in 1904 at Simms Station (Huffman Prairie), it was with a new machine, the Wright Flyer II, and in 1905, with the Wright Flyer III.

The 1903 Flyer still in the shipping crates was moved in 1915 to 15 North Broadway to a barn. The barn was eventually torn down, and Orville's Lab was built at this site where the crates were then stored. The Flyer then was finally restored at the Wright Factory in 1916. From the publication of The Wright Company, 1916, "The Beginning of Human Flight", "The rudders were badly damaged, and some other parts broken; but the machine has suffered most from going through the flood that swept through Dayton in 1913. The greater part of the machine, still in the boxes in which it was shipped from Kitty Hawk to Dayton, lay several weeks in the water and mud."

(See my post "The 1913 Dayton Flood, and The Wright Family" )

"In assembling the machine for exhibition at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the front and rear rudders had to be almost entirely rebuilt. The cloth and the main cross spars of the upper and lower center sections of the wings also had to be made new. A number of other parts had to be repaired, but most of the other parts, excepting the motor, are the original parts used in 1903. The motor now in the machine is a close copy of the 1903 motor, but was built about a year later and developed much more power than the original one....The parts of the 1903 motor are still at hand, excepting the crank shaft and fly-wheel. These were loaned some years ago for exhibition at one of the aeronautical shows, and cannot be found."(5)

The Flyer was next exhibited at the Pan American Aeronautic Exposition in New York in 1917. From The New York Times, February 9, 1917, First Wright Plane Displayed, "Orville Wright and his sister, Miss Katharine Wright, were then introduced, but Mr. Wright refused to speak....One of the most interesting features of the exhibit is the original Wright aeroplane, the first that ever flew. It is exactly as it was fourteen years ago. Contrasted to this primitive machine is the new Wright-Martin tractor biplane, with its 150 horse power motor and a speed of eighty-five miles an hour."

June 15-18th, 1918, the 1903 Flyer was displayed at the Society of Automobile Engineers Summer Meeting in Dayton, exhibited at a large hall at Triangle Park. The evening of the 18th, a banquet was given in honor of Orville Wright.

March 1919, displayed again at the New York Aero Show.

January 1921, set up at South Field Dayton for a week or two for lawsuits evidence.

Then, in October of 1924, the Flyer was displayed at the International Air Races at Dayton. Per Fred Fisk and Marlin Todd, "The Wright Brothers from Bicycle to Biplane", they indicated that "The Wright brother's original Kitty Hawk 1903 Flyer was exhibited in the old 1910 Wright Company, Huffman Prairie- Simms Station hangar at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio. This was during the International Air Races in Dayton on October 2, 3, and 4, 1924. The admission charge was to benefit the National Aeronautic Association. Orville and his sister Katharine attended these races."(6)

Then back to storage at 15 North Broadway.

1925, new cloth was installed.

As mentioned in Fisk and Todd's book, "The Wright Flyer was at Orville's Laboratory where he showed it to Charles Lindbergh on June 23, 1927. Before sending the 1903 Flyer to England, Orville Wright had the Flyer recovered again with 127 1/4 yards of "Pride of the West" muslin at a cost of $24.69."(6)

February 1, 1928, The Flyer "left Dayton via the Erie railroad en route to New York City, where if will be shipped to London...". "The biplane...landed on English soil from the Minewaska today (February 21, 1928), which sailed for England on February 11." The Flyer arrived at the Science Museum South Kensington, England, where it remained until 1948. During this time, it was removed to storage for a period of time, twice, for fear of damage during WWII. Refer to my post "Samuel Langley and the Wright Brothers" for information on why the Wright Flyer was sent to England in 1928.

Upon the death of Orville Wright in January of 1948, the question of the fate of the 1903 Flyer residing at South Kensington was still up in the air, pardon the pun. The Dayton Daily News ran the following story January 31st, 1948.

The executor's of the estate (Harold Steeper and Harold S. Miller) hired Landis, Ferguson, Bieser & Greer for assistance in settling the estate. In an interview with Co-Executor Harold S. Miller's daughter Marianne Miller Hudec, in September of 2000 by Ann Deines, Marianne quoted her father "In my opinion, Bob Landis is the best lawyer in Dayton and he is the man I want to represent me....This is a difficult case. We have the first plane coming back to the United States. I want a first class lawyer representing the estate. It turned out that Bob Landis was everything my Father thought he would be...."

Below are two letters I obtained, written by Bob Landis, addressed to Harvey Geyer and to Carl Beust. Geyer, Beust, and Louis Christman were involved in the restoration of the 1905 Wright Flyer III under the direction of E. A. Deeds, and also involved in providing an engine casting for the reproduction being prepared in South Kensington, London.

Louis Christman, writing to Guy Wainwright, President of the Diamond Chain Company, wrote the following on July 8, 1948:

December 17, 1948, the Flyer was displayed at Smithsonian's Arts and Industries Building, and remains on display at the Smithsonian to this day, per this link The 1903 Wright Flyer on Display.

As written by Tom Crouch in "The Bishop's Boys", "Daniels, at least, was uninjured. For the rest of his life, he would remind anyone willing to listen that he had survived the first airplane crash. The Wrights and their volunteer crew dragged what was left back into the hangar. The earlier aircraft, the gliders of 1900-02, had simply been abandoned at the site. This time they would ship the remains (of the 1903 Flyer) home to Dayton."(4)

|

| Artist's depiction of Wright Flyer incorrectly showing one propeller at rear and one on underside of machine. The actual details of the Flyer were kept secret by the Wright's.(7) |

The Flyer remained in the shipping crates, and was stored in the shed building behind the Wright Cycle Shop at 1127 West 3rd Street in Dayton, and there it remained for years, never to be flown again. As the Wrights continued their experiments in 1904 at Simms Station (Huffman Prairie), it was with a new machine, the Wright Flyer II, and in 1905, with the Wright Flyer III.

The 1903 Flyer still in the shipping crates was moved in 1915 to 15 North Broadway to a barn. The barn was eventually torn down, and Orville's Lab was built at this site where the crates were then stored. The Flyer then was finally restored at the Wright Factory in 1916. From the publication of The Wright Company, 1916, "The Beginning of Human Flight", "The rudders were badly damaged, and some other parts broken; but the machine has suffered most from going through the flood that swept through Dayton in 1913. The greater part of the machine, still in the boxes in which it was shipped from Kitty Hawk to Dayton, lay several weeks in the water and mud."

(See my post "The 1913 Dayton Flood, and The Wright Family" )

"In assembling the machine for exhibition at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the front and rear rudders had to be almost entirely rebuilt. The cloth and the main cross spars of the upper and lower center sections of the wings also had to be made new. A number of other parts had to be repaired, but most of the other parts, excepting the motor, are the original parts used in 1903. The motor now in the machine is a close copy of the 1903 motor, but was built about a year later and developed much more power than the original one....The parts of the 1903 motor are still at hand, excepting the crank shaft and fly-wheel. These were loaned some years ago for exhibition at one of the aeronautical shows, and cannot be found."(5)

|

| As pictured in The Technology Review, affixed in editor Fred G. Fassett's copy of Fred Kelly's "The Wright Brothers".(7) |

|

| Brochure produced by The Wright Company for display of Wright Flyer at MIT, 1916.(7) |

|

| Program of events of MIT dedication of new buildings, 24 pages, during which Wright Flyer was displayed.(7) |

The Flyer was next exhibited at the Pan American Aeronautic Exposition in New York in 1917. From The New York Times, February 9, 1917, First Wright Plane Displayed, "Orville Wright and his sister, Miss Katharine Wright, were then introduced, but Mr. Wright refused to speak....One of the most interesting features of the exhibit is the original Wright aeroplane, the first that ever flew. It is exactly as it was fourteen years ago. Contrasted to this primitive machine is the new Wright-Martin tractor biplane, with its 150 horse power motor and a speed of eighty-five miles an hour."

|

| The New York Times February 9, 1917 Aero Exposition and display of 1903 Wright Flyer.(7) |

June 15-18th, 1918, the 1903 Flyer was displayed at the Society of Automobile Engineers Summer Meeting in Dayton, exhibited at a large hall at Triangle Park. The evening of the 18th, a banquet was given in honor of Orville Wright.

|

| From Aviation and Aeronautical Engineering issue July 1, 1918. A "first model Wright machine with its 12 hp engine" was displayed, the 1903 Flyer.(7) |

March 1919, displayed again at the New York Aero Show.

January 1921, set up at South Field Dayton for a week or two for lawsuits evidence.

Then, in October of 1924, the Flyer was displayed at the International Air Races at Dayton. Per Fred Fisk and Marlin Todd, "The Wright Brothers from Bicycle to Biplane", they indicated that "The Wright brother's original Kitty Hawk 1903 Flyer was exhibited in the old 1910 Wright Company, Huffman Prairie- Simms Station hangar at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio. This was during the International Air Races in Dayton on October 2, 3, and 4, 1924. The admission charge was to benefit the National Aeronautic Association. Orville and his sister Katharine attended these races."(6)

|

| 1903 Wright Flyer on display at the March 1919 New York Aeronautical Exposition. Thank you to R. Terrell Wright of North Carolina for identifying this photo event(7) |

|

| Simms Station Hangar display of 1903 Wright Flyer during the October 1924 International Air Races in Dayton, Ohio. |

Then back to storage at 15 North Broadway.

1925, new cloth was installed.

As mentioned in Fisk and Todd's book, "The Wright Flyer was at Orville's Laboratory where he showed it to Charles Lindbergh on June 23, 1927. Before sending the 1903 Flyer to England, Orville Wright had the Flyer recovered again with 127 1/4 yards of "Pride of the West" muslin at a cost of $24.69."(6)

February 1, 1928, The Flyer "left Dayton via the Erie railroad en route to New York City, where if will be shipped to London...". "The biplane...landed on English soil from the Minewaska today (February 21, 1928), which sailed for England on February 11." The Flyer arrived at the Science Museum South Kensington, England, where it remained until 1948. During this time, it was removed to storage for a period of time, twice, for fear of damage during WWII. Refer to my post "Samuel Langley and the Wright Brothers" for information on why the Wright Flyer was sent to England in 1928.

|

| Wright Flyer at Science Museum, South Kensington, England.(7) |

|

| Wright Flyer at Science Museum, South Kensington, England, 1928.(7) |

|

| Dayton Daily News, January 31, 1948- "Will the first plane be returned to the United States? Perhaps Mr. Wright's last will and testament will provide the answer. "(8) |

The executor's of the estate (Harold Steeper and Harold S. Miller) hired Landis, Ferguson, Bieser & Greer for assistance in settling the estate. In an interview with Co-Executor Harold S. Miller's daughter Marianne Miller Hudec, in September of 2000 by Ann Deines, Marianne quoted her father "In my opinion, Bob Landis is the best lawyer in Dayton and he is the man I want to represent me....This is a difficult case. We have the first plane coming back to the United States. I want a first class lawyer representing the estate. It turned out that Bob Landis was everything my Father thought he would be...."

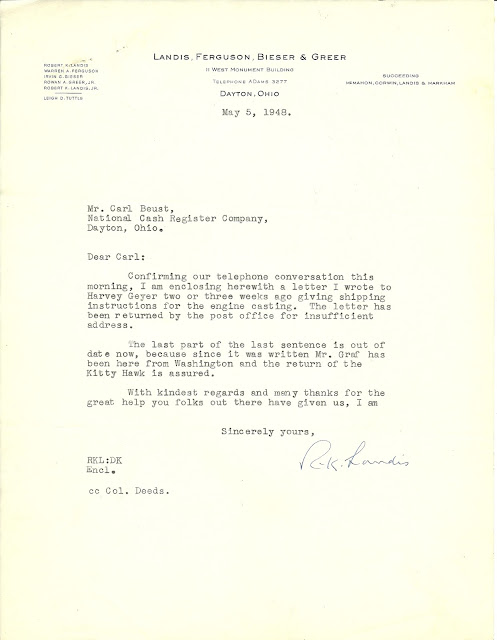

Below are two letters I obtained, written by Bob Landis, addressed to Harvey Geyer and to Carl Beust. Geyer, Beust, and Louis Christman were involved in the restoration of the 1905 Wright Flyer III under the direction of E. A. Deeds, and also involved in providing an engine casting for the reproduction being prepared in South Kensington, London.

|

| Harold S. Miller, husband of Ivonette Wright Miller (daughter of Lorin Wright).(9) |

|

| Robert Landis, attorney, confirming that the return of the Kitty Hawk is assured, May 5th, 1948(9) |

Louis Christman, writing to Guy Wainwright, President of the Diamond Chain Company, wrote the following on July 8, 1948:

December 17, 1948, the Flyer was displayed at Smithsonian's Arts and Industries Building, and remains on display at the Smithsonian to this day, per this link The 1903 Wright Flyer on Display.

Recommended links for additional reading-

Wright State University- History of the Wright Flyer

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum-The Wright Flyer First Public Display

Wright State University- History of the Wright Flyer

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum-The Wright Flyer First Public Display

Related Post- The 1903 Wright Flyer Fabric and Wood Remnants

Notes-

2/21/19 added picture of Wright Hangar, 1924, Display of Wright Flyer.

11/6/24 added John Daniels account of first flight.

Copyright 2021-Getting the Story Wright

Copyright 2021-Getting the Story Wright

References:

(1) The Wright Brothers' Aeroplane- by Orville and Wilbur Wright, The Century Magazine, September 1908.

(2) How We Made the First Flight- by Orville Wright, Flying magazine, December 1913.

(3) Dayton Daily News, December 18, 1928, "Wish Wilbur Were Here," Wright Says".

(4) The Bishop's Boys- Tom Crouch, 1989

(5) The Beginning of Human Flight- The Wright Company, 1916.

(6) The Wright Brothers from Bicycle to Biplane- Fred C. Fisk and Marlin W. Todd, 2000

(7) From Author's personal collection- press photos and vintage newspapers.

(8) From Author's collection- Dayton newspapers collected by Louis Christman following Orville Wright's death.

(9) From Author's collection- Letters archived by Louis Christman related to return of Wright 1903 Flyer.

(10) From Author's collection- From archive of Louis Christman notes concerning 1903 and 1905 Flyers.

(4) The Bishop's Boys- Tom Crouch, 1989

(5) The Beginning of Human Flight- The Wright Company, 1916.

(6) The Wright Brothers from Bicycle to Biplane- Fred C. Fisk and Marlin W. Todd, 2000

(7) From Author's personal collection- press photos and vintage newspapers.

(8) From Author's collection- Dayton newspapers collected by Louis Christman following Orville Wright's death.

(9) From Author's collection- Letters archived by Louis Christman related to return of Wright 1903 Flyer.

(10) From Author's collection- From archive of Louis Christman notes concerning 1903 and 1905 Flyers.